Here, we have the plan for Bethany Christian Services, showcased as the Michigan situation of taking in children who age out of foster care, where it seems to focus on the maximization of revenue, instead of the residuals of the peculiar institution of human trafficking.

In the spirit of fuchsia...

An Alternative for Michigan Teens Aging Out of Foster Care

You may have heard the overwhelming statistics about the number of American teens who age out of foster care without a family—more than 20,000 every year. Kids who have had a chaotic childhood and then are suddenly independent without a support system are at high risk for homelessness, incarceration, trafficking, and having children that end up in foster care. And the cycle continues.

These American teens who age out of foster care, in the context of this blog post, do not include the teens who run away, emancipate, or just get lost and forgotten in Michigan foster care. The main reason these kids had a chaotic childhood is due to the unraveling of the social security safety net, or rather privatization of poverty. These kids end up in foster care because poverty is the crime of abuse and neglect, subject to asset forfeiture of any legacies the original parents and children may have.

These American teens who age out of foster care, in the context of this blog post, do not include the teens who run away, emancipate, or just get lost and forgotten in Michigan foster care. The main reason these kids had a chaotic childhood is due to the unraveling of the social security safety net, or rather privatization of poverty. These kids end up in foster care because poverty is the crime of abuse and neglect, subject to asset forfeiture of any legacies the original parents and children may have.

There is another placement option that can provide a safeguard for teens in Michigan who turn 18 while in foster care. Young Adult Voluntary Foster Care (YAVFC) allows teens to continue in foster care up to age 21 while giving them more responsibility as they transition into adulthood. The program is voluntary and provides a turning point for teens who are almost ready to live independently but need a little more supervision and support. It is a contract, and the teen must be 18 to sign it. They can even choose to re-enter foster care if they left the system after turning 18.

They do not choose to re-enter foster care, there are no other options, well, actually there are other options.

They do not choose to re-enter foster care, there are no other options, well, actually there are other options.

- Prostitution;

- Homelessness;

- Selling drugs;

- Theft;

- Boarding rooms; or,

- Death.

Teens enrolled in YAVFC receive a bi-weekly stipend to pay their own rent and utilities. They also have access to Medicaid until age 26.

The last time I checked, most landlords and utility companies do not take bi-weekly stipends, but the agency has tapped into a new funding stream of Targeted Case Management of Medicaid fraud for a few more years.

They can also apply for funding that can help with expenses including:

The last time I checked, most landlords and utility companies do not take bi-weekly stipends, but the agency has tapped into a new funding stream of Targeted Case Management of Medicaid fraud for a few more years.

They can also apply for funding that can help with expenses including:

- Education costs: tutoring, summer school, books, and supplies

- High school graduation costs: senior pictures, yearbooks, diplomas, even prom

- College readiness costs: application fees, SAT/ACT testing fees, exam preparation classes

- Job search costs: computers, interview clothing, uniforms/footwear, special tools, licensing fees

- Housing/transportation costs: rent deposit, furniture, gas cards, bus passes

To maintain eligibility, teens must be enrolled in school, working or volunteering at least part time, a combination of school and work, or have a medical condition that prevents them from doing either.

Most kids who come out of foster care do not have access to their educational records. Then there is that issue of being homeless and trying to attend a non-traditional, private cyber school, you know, like those cyber schools that focus on the maximization of revenues that Betsy DeVos promulgates as Secretary of Education.

The concept of Post Traumatic Stress, to say the least, in dealing with children who have experienced foster care is moot to these privatized child placing agencies, because it would take away from the credibility of its operations, you know.

There is a 30-day grace period if they become ineligible at any time. Teens that are adopted, married, or in the military are not eligible.

Yes, the teems that are adopted, generally do not see a penny of the adoption subsidies provided to the adoptive parents, even if they no longer reside with the adoptive parents, whether being re-homed or just being trafficked for the purposes of eating for the day.

Most kids who come out of foster care do not have access to their educational records. Then there is that issue of being homeless and trying to attend a non-traditional, private cyber school, you know, like those cyber schools that focus on the maximization of revenues that Betsy DeVos promulgates as Secretary of Education.

The concept of Post Traumatic Stress, to say the least, in dealing with children who have experienced foster care is moot to these privatized child placing agencies, because it would take away from the credibility of its operations, you know.

There is a 30-day grace period if they become ineligible at any time. Teens that are adopted, married, or in the military are not eligible.

Yes, the teems that are adopted, generally do not see a penny of the adoption subsidies provided to the adoptive parents, even if they no longer reside with the adoptive parents, whether being re-homed or just being trafficked for the purposes of eating for the day.

The teen could be living in a licensed foster home, licensed residential care, a college residence hall, a relative or friend’s home, or in their own home—anyone they are living with must be approved through the Department of Health and Human Services (DHHS).

It is such a shame DHHS does not approve abandoned houses. In most situations, the relative or friend's home would not pass inspection, due to the elevated stress levels of child poverty in Michigan, but have no fear, the Michigan's Children''s Trust Fund continues to generate substantial returns in its overseas investments.

Each month in the program, the teen meets with a caseworker. And every six months, they review the teen’s goals and plans for the future. They assess housing and money management and work alongside foster parents, residential staff, or volunteer mentors to develop and execute a plan to prepare the teen for even more independence.

It is such a shame there have never been data produced to the successes of securing independence of these traumatized foster youth. Such publications may have a negative effect on returns of those Social Impact Bonds.

It is such a shame DHHS does not approve abandoned houses. In most situations, the relative or friend's home would not pass inspection, due to the elevated stress levels of child poverty in Michigan, but have no fear, the Michigan's Children''s Trust Fund continues to generate substantial returns in its overseas investments.

Each month in the program, the teen meets with a caseworker. And every six months, they review the teen’s goals and plans for the future. They assess housing and money management and work alongside foster parents, residential staff, or volunteer mentors to develop and execute a plan to prepare the teen for even more independence.

It is such a shame there have never been data produced to the successes of securing independence of these traumatized foster youth. Such publications may have a negative effect on returns of those Social Impact Bonds.

Teens in foster care don’t have a lot of control over their lives, and YAVFC works to gradually give them increasing responsibility as they transition to adulthood. It provides a safety net for kids who may not have family members to teach them the life skills many of us take for granted. It gives them at least one supportive adult who will be there for them and develop a relationship with them.

And, there you have it, the name of the asset forfeiture program. YAVFC.

Now, let us look at the national program the public refuses to speak upon, Interstate Compact on the Placement of Children which has no enforcement or grievance process, with no national uniformity in terms or execution of purpose, where that purpose is to layer another obfuscatory rulemaking to maximize revenues in the trafficking of tiny humans.

Now, look at the look at the Holy See and how they through the papal hat in the ring of policymaking on the trafficking of tiny humans.

It is all about the Public Private Partnerships.

$Amen$.

And, there you have it, the name of the asset forfeiture program. YAVFC.

Now, let us look at the national program the public refuses to speak upon, Interstate Compact on the Placement of Children which has no enforcement or grievance process, with no national uniformity in terms or execution of purpose, where that purpose is to layer another obfuscatory rulemaking to maximize revenues in the trafficking of tiny humans.

Now, look at the look at the Holy See and how they through the papal hat in the ring of policymaking on the trafficking of tiny humans.

It is all about the Public Private Partnerships.

$Amen$.

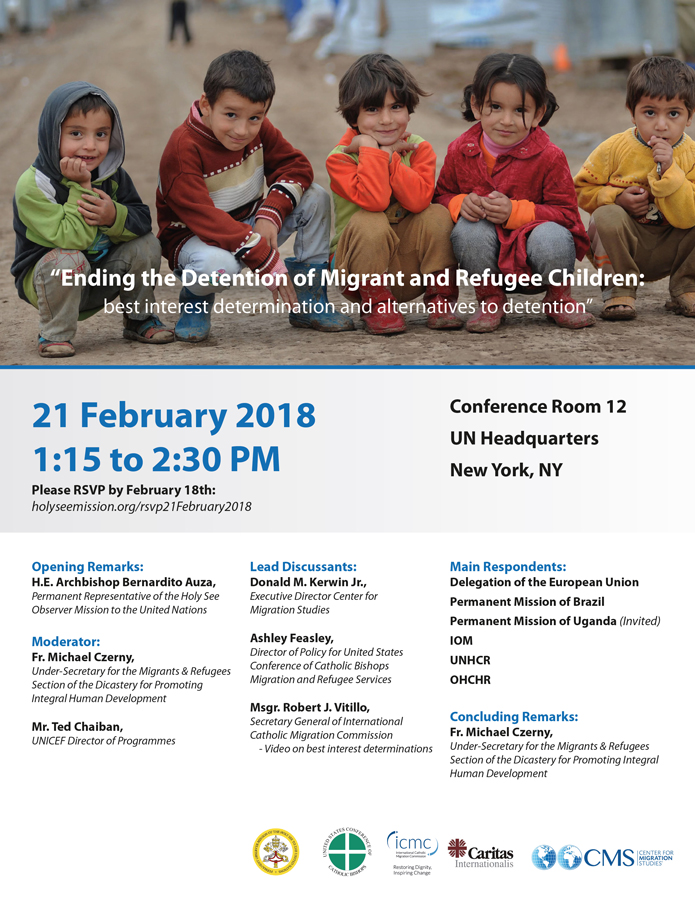

Event On Ending The Detention Of Migrant And Refugee Children

Event on

Ending the Detention of Migrant and Refugee Children:

Best Interest Determination and

Alternatives to Detention

UN Headquarters Conference Room 12

1:15-2:30 • February 21, 2018

Background: Currently, the number of migrants on the move internationally is estimated at 258 million.[1] Around the world, nearly 50 million children have moved across borders. More than half of these girls and boys – 28 million in total – were forcibly displaced, fleeing violence and insecurity.[2] Often forced to flee conflict or poverty in search of peace, security and a dignified future, children are among the world’s most vulnerable. Even when they are accompanied by their families, children are at high risk of being trafficked or otherwise exploited. En route and upon arrival to their countries of destination, they often face deportation and are often forcibly detained. Unaccompanied or separated children are confronted with even more precarious situations. In the words of Pope Francis, “They are invisible and voiceless: their precarious situation deprives them of documentation, hiding them from the world’s eyes; the absence of adults to accompany them prevents their voices from being raised and heard.”[3]

Detention is sometimes presented as a necessary tool to manage migration. Over one hundred countries continue to detain children based on their or their families’ migration status. This happens despite solid evidence of how harmful this practice is for children and their development, and despite a growing international consensus – reinforced by international and regional jurisprudence[4] – that immigration detention of children is never in their best interests – and neither is it in the best interests of States, as it is expensive, burdensome, and rarely acts as deterrent to would-be migrants.

There are reasons for hope, however. At the normative level, in the New York Declaration, States recognized these vulnerabilities and attempted to directly address the specific practice of detaining refugee and migrant children, first, by reaffirming their commitment to “comply with our obligations under the Convention on the Rights of the Child” and, second, by calling for simultaneous efforts to work “towards the ending of this practice” in full respect for their human rights and fundamental freedoms and giving primary consideration at all times to the best interests of the child.[5] At the practical level, effective alternatives to detention do exist and are being used successfully in very different contexts. These solutions can be scaled up and replicated in other countries.

While States are thus required to consider the best interests of children as a primary consideration in all decisions and to uphold their rights and fundamental freedoms without discrimination, regardless of their legal or migratory status, the measures taken do not always include “best interest determinations”. These demand a “formal process with strict procedural safeguards designed to determine the child’s best interests for particularly important decisions affecting the child,”[6] as recommended by the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees, the United Nations Children’s Fund[7] and several other multi-lateral and professional child welfare and child rights organizations. Such comprehensive reviews include an examination of the necessary pre-conditions for assuring the dignity and wellbeing of such children, including proper identification; an adequate registration process, including documentation; the opening of an individual case file; tracing; the appointment of a guardian; and the provision and monitoring of temporary care arrangements.[8]

Purpose: As we enter into the intergovernmental negotiation on the Global Compact for Migration, with formal consultations for the Global Compact on Refugees also taking place in Geneva, it is incumbent on States to discuss best practices for migrant and refugee children as they strive to find alternatives to child detention, with the goal of ending the practice of detention entirely. In other words, they must translate their commitments in the New York Declaration into concrete roadmaps supported by investments and policy change.

The Global Compacts could call on all Member States to develop National Action Plans with time-bound milestones to phase out immigration detention of children in law, policy and practice, showing how concretely they will move from using detention – even as a measure of last resort – to using alternatives and prohibiting child immigration detention. In this respect, the language proposed by the Co-Facilitators in the zero draft of the Global Compact for Migration is an encouraging sign that confirms that the above proposals are doable – the text calls for “ending the practice of child detention in the context of international migration” and providing alternatives “that include access to education, healthcare, and allow children to remain with their family members or guardians in non-custodial contexts, including community-based arrangements.”[9] As Pope Francis reminds us, “The right of states to control migratory movement and to protect the common good of the nation, must be seen in conjunction with the duty to resolve and regularize the situation of child migrants”.[10]

This panel discussion will highlight the experience of States and civil society in the dignified reception of migrant and refugee children in the field and on the borders. To do so, it will identify best practices and alternatives to detention that have been successful in ending this practice.

Speakers:

Detention is sometimes presented as a necessary tool to manage migration. Over one hundred countries continue to detain children based on their or their families’ migration status. This happens despite solid evidence of how harmful this practice is for children and their development, and despite a growing international consensus – reinforced by international and regional jurisprudence[4] – that immigration detention of children is never in their best interests – and neither is it in the best interests of States, as it is expensive, burdensome, and rarely acts as deterrent to would-be migrants.

There are reasons for hope, however. At the normative level, in the New York Declaration, States recognized these vulnerabilities and attempted to directly address the specific practice of detaining refugee and migrant children, first, by reaffirming their commitment to “comply with our obligations under the Convention on the Rights of the Child” and, second, by calling for simultaneous efforts to work “towards the ending of this practice” in full respect for their human rights and fundamental freedoms and giving primary consideration at all times to the best interests of the child.[5] At the practical level, effective alternatives to detention do exist and are being used successfully in very different contexts. These solutions can be scaled up and replicated in other countries.

While States are thus required to consider the best interests of children as a primary consideration in all decisions and to uphold their rights and fundamental freedoms without discrimination, regardless of their legal or migratory status, the measures taken do not always include “best interest determinations”. These demand a “formal process with strict procedural safeguards designed to determine the child’s best interests for particularly important decisions affecting the child,”[6] as recommended by the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees, the United Nations Children’s Fund[7] and several other multi-lateral and professional child welfare and child rights organizations. Such comprehensive reviews include an examination of the necessary pre-conditions for assuring the dignity and wellbeing of such children, including proper identification; an adequate registration process, including documentation; the opening of an individual case file; tracing; the appointment of a guardian; and the provision and monitoring of temporary care arrangements.[8]

Purpose: As we enter into the intergovernmental negotiation on the Global Compact for Migration, with formal consultations for the Global Compact on Refugees also taking place in Geneva, it is incumbent on States to discuss best practices for migrant and refugee children as they strive to find alternatives to child detention, with the goal of ending the practice of detention entirely. In other words, they must translate their commitments in the New York Declaration into concrete roadmaps supported by investments and policy change.

The Global Compacts could call on all Member States to develop National Action Plans with time-bound milestones to phase out immigration detention of children in law, policy and practice, showing how concretely they will move from using detention – even as a measure of last resort – to using alternatives and prohibiting child immigration detention. In this respect, the language proposed by the Co-Facilitators in the zero draft of the Global Compact for Migration is an encouraging sign that confirms that the above proposals are doable – the text calls for “ending the practice of child detention in the context of international migration” and providing alternatives “that include access to education, healthcare, and allow children to remain with their family members or guardians in non-custodial contexts, including community-based arrangements.”[9] As Pope Francis reminds us, “The right of states to control migratory movement and to protect the common good of the nation, must be seen in conjunction with the duty to resolve and regularize the situation of child migrants”.[10]

This panel discussion will highlight the experience of States and civil society in the dignified reception of migrant and refugee children in the field and on the borders. To do so, it will identify best practices and alternatives to detention that have been successful in ending this practice.

Speakers:

Opening Remarks

- H.E. Archbishop Bernardito Auza, Permanent Representative of the Holy See Observer Mission to the United Nations

- Fr. Michael Czerny, Under-Secretary for the Migrants & Refugees Section of the Dicastery for Promoting Integral Human Development (Moderator)

- Mr. Ted Chaiban, UNICEF Director of Programmes

Lead Discussants

- Donald M. Kerwin Jr., Executive Director Center for Migration Studies

- Ashley Feasley, Director of Policy for United States Conference of Catholic Bishops Migration and Refugee Services

- Msgr. Robert J. Vitillo, Secretary General of International Catholic Migration Commission

- Video on best interest determinations

Main respondents

- Permanent Mission of Brazil (invited)

- Permanent Mission of Uganda (invited)

- Delegation of the European Union (invited)

- IOM (invited)

- OHCHR (invited)

- UNHCR (invited)

Concluding remarks

- Fr. Michael Czerny, Under-Secretary for the Migrants & Refugees Section of the Dicastery for Promoting Integral Human Development

For more information or questions, please call the Permanent Observer Mission of the Holy See at 212.370.7885 or email Timothy Herrmann at therrmann@holyseemission.org.

Voting is beautiful, be beautiful ~ vote.©

No comments:

Post a Comment