You forgot about Amrock, Dan.

Dan Gilbert defends Quicken Loans over 'junk' bond rating

|

| Quicken Loans Technology Center in Corktown |

It is one of the city's largest employers and the biggest revenue-generator in the business empire of Dan Gilbert, the central figure in downtown Detroit's recent and dramatic turnaround.

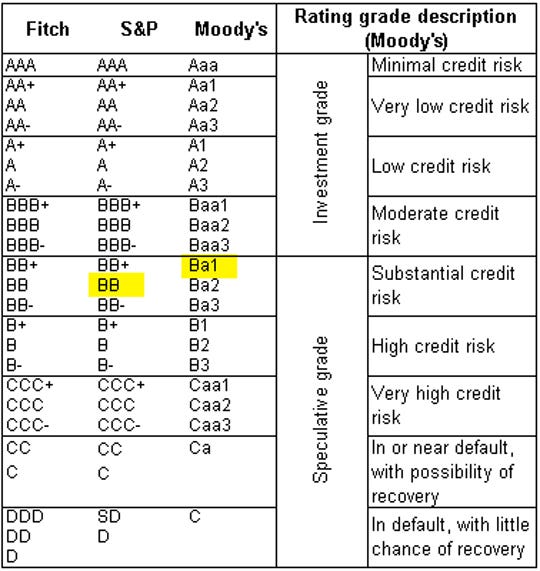

Yet in the eyes of the Wall Street credit rating agencies, Quicken Loans is still viewed as a relatively risky business and its debt is rated as below investment grade, or what is commonly called "junk" in the financial world. It's considered too dangerous for some investors such as some pension funds.

For the rating agencies, a fundamental issue is not how well Quicken is managed, but rather the nature of its business as a non-bank mortgage lender that is reliant on short-term financing — and without any bank deposits to fall back on.

During last decade's mortgage market meltdown and financial crisis, several similar lenders collapsed when their short-term borrowing arrangements dried up.

No one contends that Quicken Loans is facing any immediate danger of a cash crunch, but the rating agencies' cautionary assessment raises questions about the long-term stability of the mortgage lender's business model — as well as downtown Detroit's continued resurgence, which has relied on Gilbert's ability to finance big real estate investments.

Gilbert's real estate firm, Bedrock, owns or controls about 100 properties in greater downtown Detroit and has undertaken expensive renovations of many of them. Among other projects, the firm is building what would be the tallest skyscraper in Detroit, surpassing the Renaissance Center in height.

”If you took Dan Gilbert’s enterprises out of the equation, Detroit's downtown would be basically crawling along in rebuilding itself," said John Mogk, a Wayne State University law professor who specializes in urban development. "So If you begin to let the air out of that balloon, then everything begins to collapse.”

Two of the "Big Three" credit rating agencies have assigned junk ratings to Quicken Loans. The most recent action, in January by agency Moody's Investors Service, scored Quicken as a stable "Ba1," which is a notch below investment grade on Moody's scale.

The other agency, S&P Global Ratings, last affirmed Quicken as "BB" in 2017, or two notches below investment grade on that agency's scale. The third big rating agency, Fitch Ratings, hasn't done any in-depth scores on the company.

Gilbert defends

In a phone interview this week, Gilbert pushed back on any notion that Quicken Loans is a true credit risk.

"Our balance sheet and our liquidity is the most solid and strongest it's been since we started 34 years ago," he said Monday.

Gilbert noted how the junk category has a wide range of gradations and includes companies such as Netflix and Detroit-based Ally Financial, General Motors' former finance arm GMAC. Simply landing in junk territory doesn't mean that a company is in trouble and forced to accept exorbitant borrowing costs, he said.

Quicken had a junk rating when it did a $1 billion, 10-year bond issue in December 2017 with a 5.25% fixed interest rate.

“If you’re familiar with what people people call junk yields, (5.25%) is nowhere near that kind of thing," Gilbert said. "You see companies who are at the worst end of it getting interest rates over 12% and the companies that are at the highest notch of what you're calling junk are getting 4 or 5% interest rates."

Gilbert also emphasized how Moody's scorecard gave 65% weight to Quicken's "operating environment" in the mortgage business and only 35% to the company's balance sheet.

"What brings us down is the industry we're in," he said.

Higher risk

Credit rating agencies are tasked with evaluating the financial health of companies and governments and the riskiness of specific bonds and securities.

Companies with junk ratings typically must pay higher interest rates to borrow money than those with investment-grade ratings. That premium reflects the added risk that investors take when lending to such firms, said Sudip Datta, finance department chair at Wayne State University's Mike Ilitch School of Business.

Some investors like junk bonds because they want the higher yield.

"The rating tells investors that this is a junk-bond category, so be careful, but if you want to have higher returns, take the risk," Datta said.

Many pension funds and money market funds are not allowed to buy junk bonds.

Credit rating agencies appear to be more conservative these day when rating non-bank mortgage lenders than they were before the 2007-09 financial crisis and recession.

For example, Moody's still gave Countrywide Financial an investment-grade rating — albeit a low one — in November 2007, shortly before the mortgage giant's dramatic collapse and acquisition at a fire sale price by Bank of America the following year.

Today, Quicken Loans has a Moody's rating that is one notch below where Countrywide was in those calamitous final months.

A Moody's representative last week declined to comment on whether the agency has adjusted its rating standards for mortgage lenders since the financial crisis.

The government's official Financial Crisis Inquiry Report called the big three credit rating agencies "key enablers of the financial meltdown" for giving top ratings to mortgage-backed securities that were in actuality very risky.

"There's probably a lot of shell-shocked rating firms," Gilbert said. "If you look at the ratings of securitizations from 10, 11 years ago, you'll see a lot of investment-grade stuff that didn't turn out too well for people."

'Strengthen our liquidity'

Quicken's bonds have always been rated in junk territory. The company scored a notch below its current Moody's rating in 2015, when it issued $1.25 billion, 10-year bonds at 5.75%. Most of that money flowed to Quicken's parent company, Rock Holdings.

Gilbert said that both of Quicken's bond issues (2015 and 2017) were done to "strengthen our liquidity".

"One of the reasons was the attractive nature of the terms and the interest rate," he said. "The fact we could lock in debt for 5.25% for 10 years without covenants was something we wanted to take advantage of." (Covenants, in this case, refer to restrictions on a borrower's activities or debt levels.)

Inherent risk

In its Quicken Loans analysis, Moody's praised Quicken's "sound balance sheet" and its "conservative financial management."

It said the company's core profitability has decreased from the exceptionally high levels of 2015-16, during the mortgage refinancing boom, although Quicken is expected to stay highly profitable for the next several years.

But offsetting those positives is the inherent risk in Quicken's business model.

Unlike traditional banks that take deposits, Quicken and other non-bank lenders typically borrow money for their mortgages through so-called "warehouse" lines of credit offered by banks and other financial institutions.

Last decade's financial crisis showed how such funding models can, at times, be precarious. Lenders can pull their credit lines or other short-term financing, leaving dry the companies that depended on the money flow.

That disaster scenario happened to several mortgage lenders during the 2007-08 market collapse that had specialized in risky subprime or "Alt-A" loans, such as now-defunct American Home Mortgage and New Century Financial.

Moody's did credit Quicken for having more than 40% of its credit lines in longer term two-year durations. And it positively noted how Quicken recently began funding a small portion of its mortgages — still less than 10% — with cash on its own balance sheet.

A Free Press review of other large non-bank mortgage lenders that compete with Quicken Loans found their credit ratings to also be in junk territory — typically below Quicken's. Some of those firms had to pay interest rates between 8% and 11% in past bond issues.

Separately, the City of Detroit currently has junk ratings from at least two credit rating agencies. Detroit emerged from the nation's largest Chapter 9 municipal bankruptcy in December 2014. And Moody's downgraded Ford Motor Co. to a notch above junk in August.

Government-backed loans

Moody's said the vast majority of Quicken's mortgages have explicit government backing through Fannie Mae, Freddie Mac, the Federal Housing Administration or the Department of Veterans Affairs, which insure loans against homeowner defaults.

Quicken pools those mortgages and bundles them into securities, which the company then sells into the secondary market. Quicken uses the money from those sales to pay back the credit line funds.

Moody's said that Quicken holds its mortgages for only a few weeks, which helps to offset risks.

Other risks

The rating agency did mark down Quicken for the long-running Department of Justice lawsuit against the company. That False Claims Act case, first filed in 2015, alleges that Quicken fraudulently approved borrowers for FHA-backed mortgages from 2007 through 2011.

The company has strongly denied the allegations and, unlike other lenders, refused to settle the case with a big payout to the government. Last week, a federal judge in Detroit ordered Quicken and the Justice Department to try one more time to reach a mediated settlement.

Quicken is still the nation's largest FHA lender and, according to Moody's, has among the lowest default rates of all lenders for that type of loan.

Looking ahead, Moody's said that Quicken and other lenders could face challenges in the coming years if interest rates rise and then depress the total volume of mortgage originations.

That scenario might tempt lenders to make dodgier loans to less qualified borrowers. (a.k.a. "The Poors").

"As origination volumes decline, mortgage lenders typically migrate to riskier mortgage origination products to boost origination volumes," Moody's warned in its report.

However, Gilbert told the Free Press that Quicken, which now has a roughly 6 percent market share, would not start giving out dicey mortgages.

"The one company that didn't do those kinds of loans and survived and thrived and became the largest lender in America was Quicken Loans," he said. "So, certainly, we're not going to do that now, after we watched the whole world explode." America' largest lender, Quicken Loans, survived because it was using federal, taxpayer dollars.

Voting is beautiful, be beautiful ~ vote.©

No comments:

Post a Comment